Updated: May 7, 2017

Shiga Prefecture has three handicrafts officially designated as a “Traditional Craft” by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry (経済産業大臣指定伝統的工芸品). “Traditional crafts” as defined by the Japanese government are handicrafts used in everyday life that are largely handmade using traditional techniques and traditional materials. And they are made in a specific area.

Shiga’s three designated traditional crafts are Omi jofu hemp cloth (近江上布), Shigaraki pottery (信楽焼), and Hikone butsudan (彦根仏壇) or household Buddhist altars made in Hikone.

Japan has over thirty cities and areas that produce household Buddhist altars (“butsudan” in Japanese). Fifteen of them are officially designated as a “Traditional Craft Production Area” (伝統的工芸品産地指定) by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry. These areas include the cities of Yamagata, Kyoto, Kanazawa, Niigata, Osaka, Nagoya, Hiroshima, and Hikone. They all have been making butsudan since the Edo Period. In 1975, Hikone butsudan became Japan’s first butsudan to be officially designated as a “traditional craft.”

Hikone butsudan is thus one of Shiga’s signature products. However, Shiga actually has two traditional butsudan manufacturing areas. Besides Hikone butsudan made in Hikone and Maibara, Hama butsudan (浜仏壇), commonly called “Hama-dan” (浜壇) which is short for “Nagahama butsudan,” is made in Nagahama, Maibara, and Hikone. Although Hikone butsudan is more famous nationally due to its official designation, Hama-dan is not inferior in any way. Interesting how the Hikone butsudan and Hama-dan production bases are right next to each other, but they have different origins, histories, and designs. Since there is virtually zero English information about Hama-dan, this article will also shed some light on Hama-dan.

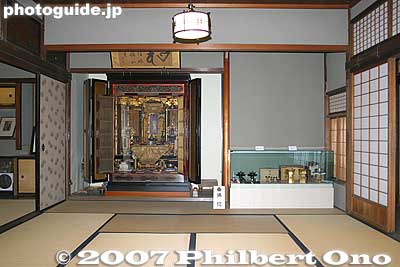

Traditional butsudan are like miniature Buddhist temples in Japanese homes. They are more common in rural (old) Japanese-style homes (with tatami mats) than in urban condominiums/apartments. A Japanese-style home may even have a Buddhist altar room called butsuma (仏間) designed for a large butsudan to fit into an alcove.

Japanese families keep a butsudan to memorialize and pray to deceased family members and ancestors. Photos of the recently deceased or small vertical tablets (ihai) inscribed with their names may adorn or complement the butsudan along with various Buddhist implements (candle holders, rice offering holders, incense burner, bell, etc.). They all direct attention to the butsudan’s central figure that is usually a Buddha statue or scroll. While praying in front of the butsudan, a family member might even “talk” or “report” to the deceased about their lives and achievements.

During the obon season in mid-August and on the anniversary of a family member’s passing, the family may hire a Buddhist priest to conduct a memorial service in front of their household Buddhist altar. The butsudan thereby unifies and bonds living family members as it reminds them of their common ancestors. And it’s much more convenient than going to the gravesite to pray to the deceased.

The practice of keeping a Buddhist altar at home is unique to Japan. They don’t do it in other Buddhist countries like Thailand. It supposedly began in the Kamakura Period (1185–1333), but it didn’t spread until the Edo Period in the 17th century. When Christians were being persecuted in Japan, butsudan is said to have spread among families who wanted to show that they were not Christian. However, fewer and fewer modern homes in Japan today are designed to have a butsudan, so fewer and fewer families buy and keep a butsudan.

Butsudan is not to be confused with kami-dana (神棚) which are household Shinto altars (miniature Shinto shrines). Keeping a household altar is a common practice in both Buddhism and Shinto. But butsudan and kami-dana altars look totally different and serve different functions.

The household Shinto altar is generally less ornate (mostly bare wood) and smaller than butsudan and are mounted high on a shelf toward the ceiling. It is usually dedicated to a local Shinto god or the god of one’s profession. Household members commonly pray to kami-dana for family safety, good health, and business prosperity. Kami-dana is quite common among business owners.

In a nutshell, butsudan are dedicated to the deceased, while kami-dana are dedicated to the living. Also, you don’t have to be Buddhist to keep a butsudan nor a Shinto believer to have a kami-dana. A home may even have both, as many Japanese worship or respect both Buddhism and Shinto. Families commonly hold both Shinto weddings and Buddhist funerals even though Shinto funerals and Buddhist weddings are perfectly fine. Even professional sumo wrestlers commonly have Buddhist funerals (sumo is a Shinto sport). When it comes to religion in Japan, things are not so black and white.

Besides serving spiritual and family functions, the traditional butsudan is a major assemblage of intricate, elaborate, and ornate artwork. It provides the livelihoods of highly-skilled traditional craftsmen and artisans required to make a butsudan. There are at least seven types of traditional craftsmen involved in making a butsudan: Cabinet maker (kiji-shi 木地師) who makes the wooden exterior cabinet, inner altar builder (kuden-shi 宮殿師) who makes the butsudan’s inner sanctum complete with a temple-like roof, woodcarver (chokoku-shi 彫刻師) who carves the transoms and Buddha statue, lacquer painter (nuri-shi 漆塗り師) who lacquers the cabinet, gold leaf gilder (kinpaku-oshi-shi 金箔押し師), metallic ornament maker (kazari-kanagu-shi 錺金具師) who makes metallic fittings and ornaments, and maki-e artist (makie-shi 蒔絵師) who creates lacquer decorations with sprinkled gold powder. The butsudan parts are then assembled by the butsudan shop that received the customer’s order. The best traditional craftsmen can also be certified with the official title of “Traditional Craftsman” (伝統工芸士) from the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry.

Hikone butsudan is classified as a kin-butsudan (gold Buddhist altar 金仏壇) in reference to the abundant use of gold leaf (made of 95%+ pure gold). Like Kanazawa butsudan in Ishikawa Prefecture (famous for gold leaf) and Kyoto butsudan, Hikone butsudan looks very gold and is regarded as a high-end butsudan. The lacquer is glossy and the wood is usually hinoki cypress, zelkova (keyaki), or Japanese cedar.

Hikone butsudan originated in the mid-Edo Period (17th-18th centuries). Traditional craftsmen such as cabinet makers, lacquerware artists, and metallic ornament makers who had produced samurai swords, helmets, armor, etc., switched to making Buddhist altars as a peaceful pursuit during the peaceful Edo Period. It started with a lacquerware merchant who made a butsudan after learning from Kyoto butsudan sometime during 1624-44. As household Buddhist altars became more common, the Hikone daimyo (Ii Clan) officially sanctioned and protected the butsudan makers’ livelihoods. Many of these craftsmen lived in the Nanamagari area (七曲がり) of Hikone where a number of butsudan craftsmen and shops still remain while other craftsmen are scattered about in Hikone. In Nanamagari, you can visit butsudan shops and perhaps see an artisan at work or take a workshop in one of the butsudan crafts. In autumn, they hold the Nanamagari Festa (七曲がりフェスタ) with butsudan craftsmen demonstrating their art and offering hands-on lessons for the public.

With the backing of the local daimyo, Hikone’s butsudan industry developed into an efficient production system and became one of Hikone’s major traditional industries. After World War II, Hikone butsudan makers established their own guild and product inspection system to improve and assure the quality of their products. Traditional butsudan are usually signed and dated by the maker or artisan.

Meanwhile, Hama-dan Buddhist altars have kind of a confusing history since there was the original Izumi-dan (和泉壇) which has since been grouped together with Hama-dan. Technically, Izumi-dan and Hama-dan have separate lineages and both still exist, but I’m told Izumi-dan is quite rare now due to its high price range and it has since been commonly called Hama-dan. Izumi-dan has a unique kind of sculpture or style that a butsudan expert can distinguish from a Hama-dan. Izumi-dan is named after a prominent Nagahama carpenter and woodcarver named Fujioka Izumi (藤岡 和泉 1617–1705) who specialized in carving lotuses and clouds. He gained fame after creating highly-rated woodcarvings for Izumi Shrine in Nagahama. He made butsudan as well.

Izumi favored making butsudan with less gold leaf and more bare wood than Hikone butsudan and Kyoto butsudan. For example, the wood-carved transom (sama) on the altar’s top edge is bare wood and not gold like on Hikone butsudan. He used zelkova (an expensive and durable wood) for the transom and hinoki cypress for the cabinet and included much maki-e lacquer art.

Another distinctive feature is the Hama-dan’s inner altar roof. It looks a like castle roof with multiple ridges and decorative triangular gables called chidori-hafu (千鳥破風). They make the butsudan look very dignified.

Izumi’s descendants/associates also made the first hikiyama floats for the Nagahama Hikiyama Matsuri in the 18th century when kabuki became popular. The design of the hikiyama floats was modeled after the Izumi-dan Buddhist altars. In the photos above, you can how the roof design of the hikiyama float and butsudan are similar. Hikone butsudan has a different type of inner roof.

The Fujioka family helped to build and maintain the ornate Nagahama hikiyama floats. However today, the Fujioka family is no longer in this business and the floats are maintained by butsudan craftsmen.

Despite the different designs of Hikone butsudan and Hama-dan, both types can be configured to suit any Japanese Buddhist sect. Although the Jodo Shinshu Sect favors gold butsudan (like Hikone/Kyoto butsudan), a Jodo Shinshu family can still use a Hama-dan instead. I’m told that most Jodo Shinshu families in Nagahama and Maibara have a Hama-dan. (The butsudan in my home in Shiga is a Hama-dan as well.) Hama-dan is also reputed to be bigger than Hikone butsudan. Although I’m sure a (rich) customer can custom order a Hikone butsudan in any large size. I’m told that Hikone butsudan has a nationwide market base, while Hama-dan customers are mainly limited to northern Shiga.

Even though they are neighbors, it’s nice that Hikone butsudan and Hama-dan have retained their unique characteristics all these centuries. They also share some of the craftsmen who make butsudan parts for both Hikone butsudan and Hama-dan.

In September 2015, we visited one such craftsman, a very accomplished and versatile 70-year-old woodcarver (and painter) named Mori Tesso (森 哲荘) who lives and works in Kami-nyu (上丹生) in the city of Maibara. Out of the seven traditional butsudan craftsmen, I was most interested in the woodcarvers. After all, they make the Buddha statues that become the focal point of the butsudan. An online search led me to Mori Tesso at Mori Chokokusho (森彫刻所), a modest woodcarving studio next to his house. He has been a woodcarver in Kami-nyu for 55 years since age 15, right after junior high school. I got an exclusive interview and tour of their studio.

Kami-nyu is a small, rural enclave of butsudan craftsmen in a quiet, mountainous neighborhood in the Samegai area (on the way to the trout farm). There are cabinet makers, woodcarvers, gold leaf gilders, lacquer painters, etc. To have all these traditional craftsman in one place is quite rare in Japan. They make butsudan parts for both Hikone butsudan and Hama-dan, although such work has decreased dramatically.

Kami-nyu’s history goes back to the Tempyo Period (729–749) when a clan related to the Imperial Court lived in this area. Through their connections, they were exposed to cultural information and techniques from Korea and China. Kami-nyu thereby developed as a center of highly refined culture. In the early 19th century, two Kami-nyu teenage lads, 14-year-old Ueda Yusuke (上田勇助), who was the son of a shrine/temple carpenter, and friend Kawaguchi Shichiemon (川口七右衛門), spent 12 years in Kyoto to learn traditional woodcarving. When Yusuke came back to Kami-nyu, he worked as a woodcarver for local temples. Since the area was mountainous with little farmland, people in Kami-nyu made a living cutting trees and making woodcarvings for temples, shrines, and festival floats.

In the late 19th century (mid-Meiji Period), Yusuke’s son and successor (Yusuke II) ventured to make woodcarvings for Hama-dan, further refining his skills. Other butsudan craftsmen from different disciplines also started to settle in Kami-nyu. Kami-nyu thereby transformed from a woodcarvers’ neighborhood into a traditional crafts village that continues today. It’s a family business or cottage industry and most everything is handmade. They work separately, but as a team. There are no large, mass production factories. (Yusuke’s current descendants are no longer woodcarvers.)

Kami-nyu has a few butsudan shops (仏壇店) where you can custom order a butsudan to suit your budget and preferences. Many customers have their traditional butsudan custom-made. The shop will then mobilize and coordinate the traditional craftsmen in Kami-nyu to make the butsudan parts to be assembled by the shop.

Although the Kami-nyu craftsmen’s mainstay used to be making butsudan parts, their numbers have sadly shrunk dramatically due to a lack of work. The surviving ones now do mostly other work, any type of job that matches their skills (and fees). It could be a transom in a new house, restoration or repair work for temples, shrines, large altars, butsudan, kami-dana, and festival floats. They are highly versatile craftsmen.

Mori Tesso is a second-generation Kami-nyu woodcarver taking after his late father Hideo (秀男) who started the family trade. He was pretty much forced into the profession by his father who insisted that there were skills that can only be acquired at a young age. Tesso originally did not care so much for woodcarving and wanted to continue on to high school instead. However, after learning the craft from his father and older brother Nozomu, Tesso came to love woodcarving and feels fortunate to have pursued it. Look at his works and you will see that he is very good.

Hideo, born in 1900, apprenticed under a butsudan woodcarver in Kyoto after elementary school. He eventually became a master woodcarver. The post-war years were tough for him as people were too poor to buy butsudan. Old butsudan were often sold to feed the family.

As Japan recovered and people could afford to buy butsudan again, Hideo worked in Kyoto and trained many apprentices including his elder son Nozomu who started in 1951 after junior high school. Nozomu has been carving for over 60 years and lives in Kami-nyu.

Unfortunately, Hideo died at age 64, only three years after Tesso started carving. Tesso was quite saddened by his father’s passing and started dabbling in drawing and painting. But after getting married in 1973, he buckled down and pursued butsudan woodcarving seriously for a steady income. It takes at least 10 years to master the craft, and another 10 years to become a more versatile woodcarver.

He soon had two sons, Yasuichiro (靖一郎) and Tetsuo (徹雄), both of whom became woodcarvers themselves. Yasuichiro started training under his father and Uncle Nozomu at age 20 after graduating from a junior art college. Younger son Tetsuo apprenticed under his Uncle Nozomu as a woodcarver after high school. Both Yasuichiro and Tetsuo have been been carving for over 20 years now, so both are already master woodcarvers. Like his father, Yasuichiro has been certified by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry as a Traditional Craftsman for Hikone butsudan (彦根仏壇伝統工芸士). (There is no such certification for Hama-dan.) The two sons were not home during our visit so I didn’t get to meet them.

The Moris live along the river flowing through Kami-nyu and Samegai. Their immediate neighbor is another craftsman and there is also butsudan shop right nearby. Their woodcarving studio is in a separate building next to their home. The studio is a fairly spacious room for three woodcarvers to work. They all face a window so they can look outside once in a while. Tesso carves while sitting at a low table which is actually a thick plank of wood. He sits on the floor, but his legs stretch out into a sunken pit. He has many little drawers for an arsenal of many different chisels. Kami-nyu is a quiet and relaxing place to do intricate work.

He showed us a variety of wood sculptures. He sketches the carving on the wood or paper, then makes a rough carving with a hammer and chisel. The final stages are fine carving. If there is a human face, he carves it last, as it is the most difficult part to carve. They don’t use sandpaper, etc., to smooth the surface either. It’s all smoothed with a chisel. This skill itself takes a few years to master.

Besides butsudan carvings, the Moris carve sculptures for shrines and temples (roof beams, transoms, etc.), wooden signboards for businesses, wooden picture frames, and festival floats. They can basically carve whatever the customer wants. They also repair butsudan sculptures. They do have ready-made sculptures for sale, but it seems that they mainly produce custom orders.

Tesso is a very, very versatile artist. He can carve all kinds of things. Just look at their website gallery for samples of their work. They also sell their work online via Yahoo Japan. An incredible variety. The Mori family also carved part of the impressive woodcarving mural displayed at Maibara Station’s east entrance. The mural shows Maibara’s major sights like Mt. Ibuki (top center) and Mishima Pond carved in wood.

After showing us his workshop, he brought us into his home where we saw a large Hama-dan in his Buddhist altar room (top photo). He made the butsudan with all the woodcarvings except for the Buddha statue that was carved by his father. Tesso told me that one customer saw this butsudan and immediately decided that he wanted one exactly like it. So Tesso had one made exactly like it. The cost? Ten million yen (!).

Indeed, high-end (i.e. large size and ornate), traditional butsudan can cost more than the top-of-the-line Mercedes-Benz luxury car (S-Class). On the other hand, there are also simplified and compact butsudan called “modern butsudan” (モダン仏壇) which cost a lot less than traditional butsudan. Modern butsudan are basically wooden cabinets sans woodcarvings and major artwork. Average size models (about 60 cm high) can cost around ¥150,000 or more, but when you throw in the standard implements (rice offering holders, candle holders, bell, etc.) and Buddha figure or scroll, it can total around ¥300,000 or more. Modern butsudan are geared for city dwellers and condos where space is limited.

Also, there is a lot of imported butsudan (or parts) from countries like China and Vietnam where labor is much cheaper than in Japan. Imported butsudan started to spread in Japan from the 1990s. They now account for about 70 percent of the butsudan sold in Japan.

Tesso tells me that these imported butsudan pose the biggest challenge or competition to the traditional craftsmen. Sadly, the number of traditional butsudan craftsmen has decreased significantly and the Moris no longer carve for butsudan that much. He says that they have been adapting and adjusting to such market conditions. Traditional craftsmen in Japan are now basically relegated to the high-end market. They are also supported by purists who still favor “Made in Japan” butsudan and other crafts, citing subtle differences in the artwork of imported models. For example, dragon sculptures on imported butsudan may look too “Chinese.” Some butsudan shops proudly indicate that their butsudan are “Made in Japan.” Otherwise, we cannot tell if it is imported or not.

During a quick tour of butsudan shops in Tokyo, I was surprised to see so many modern and imported butsudan. Even though the modern ones are more suited for urban families and Western-style homes, it’s still sad to see how the traditional butsudan are being squeezed out. The lower prices of modern/imported butsudan are no doubt very tempting for the average worshipper.

People in the market for a butsudan have a very, very wide selection. Whether it’s traditional or modern, large or small, cheap or expensive, or plain or ornate. Unlike electrical appliances, cars, and furniture, there are no corporate brands of butsudan. There are only traditional regional brands and anonymous brands (modern or imported). Hikone butsudan and Hama-dan are no doubt among Japan’s elite butsudan that can last for generations.

Even if you’re not Buddhist/religious or have no plans to buy a butsudan, I hope this article makes you appreciate the fine artwork that goes into a traditional butsudan and piques your interest to try and identify any butsudan you might sooner or later see in Shiga.

*Special thanks to Mori Tesso for showing us his workplace and sculptures and to Yasuichiro for answering my supplemental questions.

Major references for this article:

- Mori Chokokusho

- http://hikone-butsudan.net/

- Interview with Morioka Eiichi (森岡栄一), curator at Nagahama Castle History Museum.

- http://butsudan-prem.com/production/

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (「伝統的工芸品」とは)

- Daruma Magazine, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Summer 2008), A Family for All Seasons —Mori Family Carvers—, by Carla Eades & Nishiyama Yuriko

- Making a Hikone Butsudan by Carla Eades

- http://www.inouebutudan.com/english/craft.html